Weekly Notes: legal news from ICLR — 19 November 2018

In this week’s roundup we get cheesed off over copyright, divided over Brexit, banged up for data abuse, intolerant over evidence disclosure, and better informed about the courts, among other things.… Continue reading

Intellectual property

No accounting for taste in copyright law

Lovers of processed food may be cheesed off with the judges of the European Court of Justice, who last week decided that the taste of a processed cream cheese product cannot be protected by copyright law.

In Levola Hengelo BV v Smilde Foods BV (Case C‑310/17) [2018] WLR(D) 696 the Court of Justice held that Parliament and Council Directive 2001/29/EC (on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society) precluded the taste of a food product from being protected by copyright and prevented national legislation from being interpreted in such a way. The reasoning, as captured the ICLR reporter’s case summary, is that

For there to be a “work” as referred to in the Directive [consisting of an original creative expression of an author’s intellect] the subject matter protected by copyright had to be expressed in a manner which made it identifiable with sufficient precision and objectivity, even though that expression was not necessarily in permanent form. The taste of a food product could not, however, be pinned down with precision and objectivity, unlike, for example, a literary, pictorial, cinematographic or musical work. The taste of a food product would be identified essentially on the basis of taste sensations and experiences, which were subjective and variable since they depended, inter alia, on factors particular to the person tasting the product, such as age, food preferences and consumption habits, as well as on the environment or context in which the product was consumed.

On their Out-Law blog, solicitors Pinsent Masons commented:

“The ruling emphasises the need for legal certainty when affording works copyright protection and means that food producers are free to compete and offer similar products,” said Iain Connor, an expert in intellectual property law at Pinsent Masons, the law firm behind Out-Law.com.

He added:

“Recent changes to trade mark law mean that trade marks no longer have to be capable of being ‘graphically represented’, but Connor said those reforms do not necessarily open the door for food manufacturers to gain trade mark protection for the taste of their products.

‘A trade mark office would be loathe to accept and protect a pot of spreadable cream cheese dip given that it is not clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective,’ Connor said.”

On the IP Kat blog, Eleonora Rosati noted that

“The case is important for a number of reasons, and especially because it is probably the first time that the CJEU has been given directly the chance to tackle the notion of ‘work’ under the InfoSoc Directive (but, I would say, the overall EU copyright acquis).”

Her analysis, which describes parts of the judgment as “headache-inducing”, is worth reading in full to understand why she finds aspects of the court’s reasoning unsatisfactory.

The Levola Hengelo CJEU decision: ambiguities, uncertainties … and more questions: As… https://t.co/7msJGnopwo

— The IPKat (@Ipkat) November 13, 2018

Brexit

Deal or no deal?

Such is the state of uncertainty around Brexit at the time of writing that one might equally be asking May or No May? — and speculating as to who will be the Prime Minister if and when we exit the EU next March.

At any rate, this much is clear. On 14 November 2018 the Prime Minister secured Cabinet approval for a Draft Agreement on the Withdrawal of the UK from the EU, which was duly published by the Department for Exiting the European Union and also by the the EU Commission. There was then a series of ministerial resignations, including most notably the Secretary of State for the department responsible for having negotiated the agreement, Dominic Raab. (You may recall how, last week, we reported his admission that he had not appreciated the geographical imperative driving so much trade through the Dover-Calais crossing).

The Draft Agreement is now, thanks to section 13 of the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, subject to a parliamentary vote. A large number of MPs or factions within the House of Commons have indicated that they will not approve the agreement. Some have indicated a desire to renegotiate the deal (they have 130 days left to do so); others, a desire for a change of leadership or government; others again, a desire for a second vote, incorporating one or more deal options as well as the possibility of a reversal of the original decision to leave the EU. Few of the MPs expatiating about these options appear to have studied the agreement itself in detail. But, luckily for us, a number of legal commentators have:

Obiter J on the Law and Lawyers blog has a series of post on different aspects of the agreement, starting here: Draft Withdrawal Agreement — November 2018 — №1

David Allen Green, posting on his Jack of Kent blog, explains Why the draft withdrawal agreement may be the only responsible option

Robert Craig on the UK Constitutional Law blog, asks What Happens Constitutionally If the Draft Withdrawal Agreement Is Voted Down?

For convenience, Dr Holger Hestermeyer of King’s College London, prepared a handy table of contents to the 585-page Agreement:

The Withdrawal Agreement is not accessible, you say? For my orientation and yours I have drafted a table of contents. Enjoy. (Maybe that’s not the right word. Suffer less?) pic.twitter.com/2IHYy8XRLS

— Holger Hestermeyer (@hhesterm) November 18, 2018

Data protection

Prison for computer misuse

The Information Commissioner’s Office has for the first time used its powers as a corporate prosecutor under the Computer Misuse Act 1990 to secure a conviction resulting in a prison sentence for misuse of personal data. Mustafa Kasim, who used his colleagues’ log-in details to access a software system that estimated the cost of vehicle repairs, was subsequently sentenced in the Crown Court to a term of six months’ imprisonment.

An announcement from the ICO explained that:

“Kasim, who worked for accident repair firm Nationwide Accident Repair Services (NARS), accessed thousands of customer records containing personal data without permission, using his colleagues’ log-in details to access a software system that estimates the cost of vehicle repairs, known as Audatex.

He continued to do this after he started a new job at a different car repair organisation which used the same software system. The records contained customers’ names, phone numbers, vehicle and accident information.

NARS contacted the ICO when they saw an increase in customer complaints about nuisance calls and assisted the ICO with their investigation.”

Commenting on the case, Jon Baines of Mishcon de Reya explained that the offences for which the ICO is expressly empowered to prosecute under data protection laws up to and including the Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA) have not carried custodial sentences. Nor has it sought to extend its remit to statutory offences outwith its express powers, such as sections 1 to 3A of the Computer Misuse Act 1990 (CMA), which would often involve misuse of personal data, and which are punishable in some cases with up to 14 years imprisonment.

“However, since the Supreme Court case of R v Rollins [2010] UKSC 39; [2010] Bus LR 1529, it has been clear that any corporate body, is, in general terms, entitled to bring a prosecution for any offence, subject to statutory restrictions and conditions. While prosecutions under the DPA are limited to being brought by the ICO (or with the consent of the Director of Public Prosecutions), prosecutions under the CMA are not.”

Baines noted that

“As recently as 2017 the ICO was saying that investigations under the CMA were ‘outside of its remit’. Clearly, it no longer thinks this is the case. Not every data protection infringement will constitute an offence under the CMA, but nonetheless it seems pretty clear that there is now a new prosecutor in town.”

An example of the more conventional prosecution route under the CMA was that by the National Crime Agency of the two men convicted for hacking into the website of the telecoms giant TalkTalk and stealing customer bank details in 2015. The Guardian reports that Matthew Hanley, 23, and Connor Allsopp, 21, were jailed this week for terms of 12 and 8 months respectively.

Judiciary

Lord Chief Justice’s 2018 Annual Report

This week the Lord Chief Justice (pictured) issued his annual report for 2018. It does not make for comfortable reading. He said:

“I view the low levels of morale within the judiciary with considerable concern. The poor state of many of our buildings is a contributing factor. So too is the increasing workload in most jurisdictions, and the reduction and high turnover of staff.”

Not surprisingly, there has been an ever-worsening recruitment crisis, with “a need to recruit unprecedented numbers of judges over the next couple of years”.

But there is some good news. The judiciary have become “more diverse in age, background, gender and ethnicity”. There has been improvement in the way they have been involved in the modernisation of the courts. And as their leader, Lord Burnett CJ has been

“more impressed than ever by the extraordinary dedication of our judges and magistrates to the administration of justice and the public we serve in increasingly difficult circumstances.”

Lord Burnett said he was concerned that people’s views continued to be “informed by outdated media stereotypes” about the judiciary, and he said more would be done to promote understanding, including in schools. The film of The Children Act, he said, “accurately highlighted some aspects of the work done in the Family Courts”. Moreover, “Judges also increasingly talk to the media about the realities of judicial life.”

Among the examples of judicial engagement with the media and public, he cited the press conference given by Sir James Munby when retiring as President of the Family Division in July 2018 (which was reported by the Transparency Project) and the live streaming of hearings in the Court of Appeal, which began in the Civil Division for the first time last week. Footage from the Criminal Division was used in the ITV documentary Inside the Court of Appeal (reviewed here on the ICLR blog).

The report goes on to deal with developments in various different areas of work, such as criminal, civil and family, in more detail. You can download the report.

Employment

Judicial whistleblower’s call for help

Support is being sought via a crowdfunding appeal to enable Claire Gilham, a district judge who worked in Warrington county court, to bring to the UK Supreme Court the question whether she was a “worker” who should be protected under employment law as a whistleblower.

According to her CrowdJustice campaign, Whistle-blowing rights for Judges, she has been engaged in

“a long personal battle to combat a lack of transparency surrounding her complaints over the running of the court where she was a sitting judge.

On a court closure a lack of agreed standards for service delivery and hierarchical but data-poor judicial administration led to bullying, overload, and highly unsafe working conditions. Reporting of mistakes was sanctioned while shortcuts were mandated that affected the administration of justice. […]

In pursuing the complaint first internally and then through the courts, Claire was put through a forced retirement on ‘ill-health’ grounds which has been challenged. It was put to her that she would be required to the sign a Non-Disclosure Agreement — a course which she maintains would have involved a breach of her judicial oath. She now faces professional, financial and personal ruin for fighting a battle that she believes is her ethical duty.”

She claims that her treatment amounted to unlawful public interest disclosure detriment, contrary to section 47B(1) of the Employment Rights Act 1996 (as inserted by Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998):

“A worker has the right not to be subjected to any detriment by any act … by his employer done on the ground that the worker has made a protected disclosure”

— or in other words, for whistleblowing. But the Ministry of Justice maintains that she was not a “worker” employed by them within the meaning of section 230(3) of the 1996 Act.

An employment judge found, on a preliminary issue, that district judges were office-holders appointed by the Queen; that they were paid a salary determined annually by the Lord Chancellor, there being no element of negotiation; and that they held office until the age of 70 and could only be removed earlier in limited circumstances and with the concurrence of the Lord Chief Justice. The employment judge held that there was no intention to create a contractual relationship, the duties being defined by the statutory role of the district judge and any terms of service extending beyond the immediate requirements of the role being incidental to the office held; and that, accordingly, the claimant did not come within the definition of “worker” in section 230(3), so as to be protected under section 47B. Both the Employment Appeal Tribunal, Gilham v Ministry of Justice [2017] ICR 404, and the Court of Appeal [2018] ICR 827 affirmed that decision, notwithstanding the effect of the Human Rights Act 1998.

Now she wants the point considered by the Supreme Court, who gave permission to appeal on 15 May 2018. But, reports the Guardian,

“Because her protracted case has proved so expensive, Gilham has mortgaged her home to pay for legal bills. She has launched an appeal on the CrowdJustice website to seek support and raise awareness of the issues.

‘It’s a test of whether judges really enjoy protection or whether the [whistleblowing] exemption exists primarily to protect the administration,’ she said.”

You can support her appeal here.

Family

Family Justice Observatory

Sir James Munby, who recently retired as President of the Family Division, has been appointed chair of the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory, which has been established to “support the best possible decisions for children by improving the use of data and research evidence in the family justice system”.

According to the Nuffield announcement,

“Sir James’s first priority as Chair will be to lead an open recruitment process for members of a new governing board to support the creation and development of this important organisation.”

Crime

Disclosure failings review

The Attorney General, Geoffrey Cox QC, published the government’s Review of the efficiency and effectiveness of disclosure in the criminal justice system, and found it sub-standard in many respects. The government has sworn to adopt a zero-tolerance approach to the problem, albeit without apparently departing from its zero-increase approach to funding*.

“The Review found that the duty to record, retain and review material collected during the course of the investigation was not routinely complied with by police and prosecutors. Disclosure obligations begin at the start of an investigation, and investigators have a duty to conduct a thorough investigation, manage all material appropriately and follow all reasonable lines of inquiry, whether they point towards or away from any suspect. The Review found that this was not happening routinely in all cases. At the least this caused costly delays for the justice system and at worst it meant that cases were being pursued which the evidence did not support. The impact of these failings caused untold damage to those making allegations and those accused of them.

The Government’s Review has concluded that to enable lasting change, there must be a ‘zero tolerance’ culture for disclosure failings across the police and the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS).”

*To be fair, the full report (PDF) does mention the possibility of providing more funding to the police through the Police Transformation Fund for technological developments that may help improve its performance in relation to disclosure.

Courts

CA Civil Division live streaming

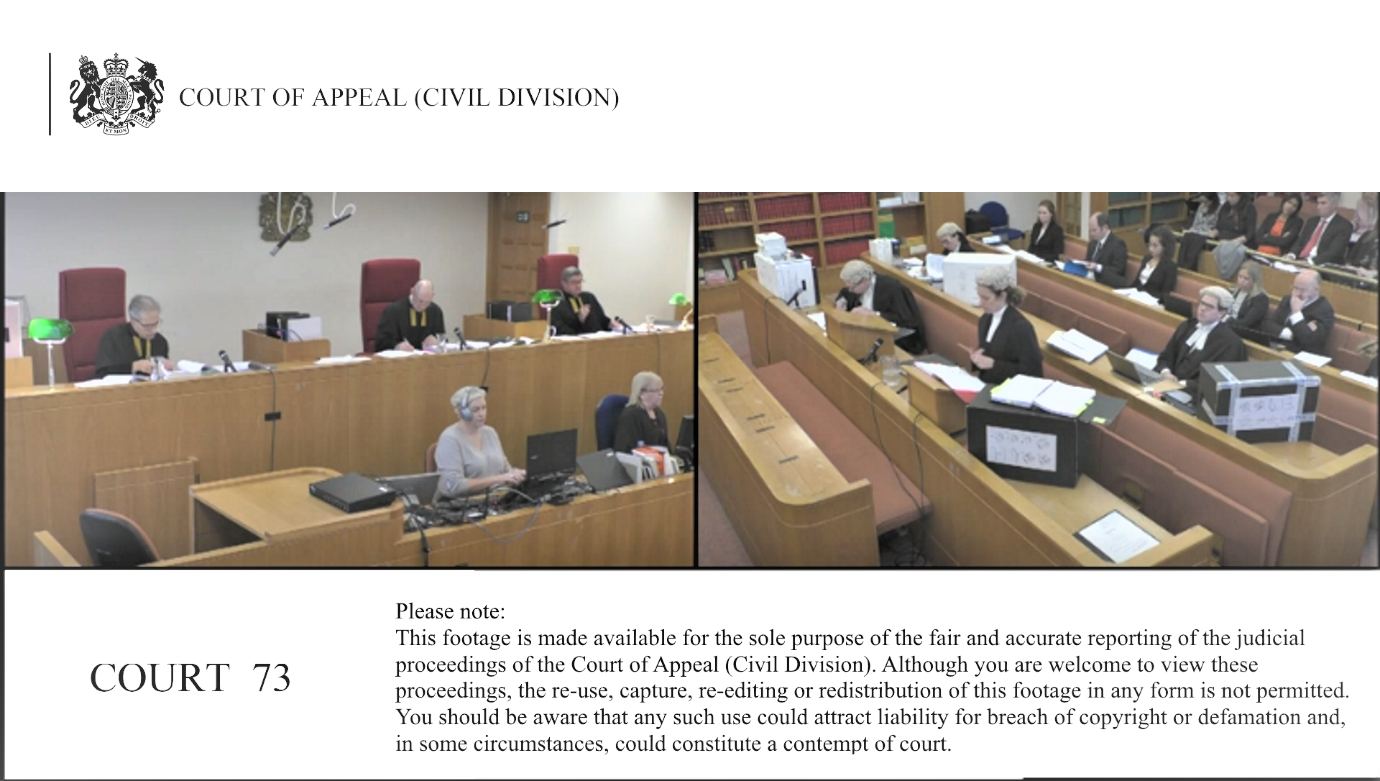

In another boost for open justice and public legal education, the Court of Appeal, Civil Division allowed cameras in court for a live streamed broadcast via YouTube, through a link embedded on the Judiciary website. The announcement by the Judiciary Office stated:

“Live-streaming of selected cases will begin on 15 November 2018 to improve public access to, and understanding of, the work of the courts.

In the case selected for the public pilot, West Ham United and E20 which manages the former Olympic stadium are in dispute as to the seating capacity that should be made available to the football club for its home fixtures at what is now known as the London stadium in Stratford, East London.”

The broadcast, when it began, was displayed on a split screen, showing the three judges in one frame, and counsel’s row in the other. There was also a clear warning displayed, beneath the split views of the court in progress, stating that the footage was being made available for “the sole purpose of fair and accurate reporting” — presumably on the basis that the relay was itself the reporting, rather than being merely an aid to reporting; otherwise it would have added “and for public access and transparency” or words to that effect.

It was soon apparent that however modern the filming process was, the conduct of the appeal itself was thoroughly old-school, with paper bundles in lever arch files and periodic references to “bundle 2, tab 5” and the sound of shuffling papers. Whether this will promote public legal education remains to be seen — the relay was suspended whenever the hearing was adjourned

— but as a proof of concept it was reassuring. We can’t reproduce any image of the actual live broadcast, even in still form, because section 41 of the Criminal Justice Act 1925 forbids it. (The split-screen still above is a publicity image taken from the Judiciary’s website page.) However, the recording appears to have remained, and can be replayed, on the YouTube page. That accords with the practice in the UK Supreme Court, but is a first for the Court of Appeal.

Flexible Operating Hours

Earlier attempts by Her Majesty’s Court and Tribunals Service (HMCTS) to trial flexible operating hours (FOH) in the court were suspended last year following a consultation and review. Now, it seems, they are back, albeit in a more limited pilot. As HMCTS explain in an FOH Prospectus for Civil and Family Court Pilots (November 2018):

“We listened carefully to the concerns that were raised, particularly by those in the legal profession. We agree that there are currently particular pressures in the criminal jurisdiction and have therefore taken the decision to not proceed with pilots in the Magistrates’ and Crown Courts. We have decided to proceed only with two pilots, in the Civil and Family Courts.”

There has been limited enthusiasm for the idea from most professionals. The Bar Council and the Family Law Bar Association put out a joint statement about the proposal. The chair of the Bar, Andrew Walker QC welcomed the decision not to proceed in the criminal courts, and said the civil and family court pilots would be closely monitored. He added:

“we remain very concerned about the implications of early starts and late finishes, and there are many questions still to be answered about the practicality of these revised proposals.”

Frances Judd QC, Chair of the Family Law Bar Association, said:

“We intend to work closely with the Bar Council and to monitor the pilots carefully, in particular as to the effects upon family barristers who are already working to capacity, and often have to travel considerable distances to court. We are assured that there will be an independent evaluation, to which we will be invited to contribute.”

In their prospectus HMCTS insist that:

“We have not made any decisions to roll out FOH nationwide or in other jurisdictions. We would only do so based on robust evidence and data gathered through piloting with a comprehensive evaluation of the impacts, the costs, and the benefits across the justice system understanding the effects of the reform programme.”

The stated aims of FOH are to make better use of the courts estate, and to offer litigants the opportunity of attending court outside normal working hours. The announcement airily suggested that it would give such litigants “greater access to hearings that can fit around their busy lives”. However, given the cost of litigation, one might have thought most litigants would want to take time to do it properly and not squeeze it in like an afterthought.

Dates and Deadlines

‘Ask a Justice’

UK Supreme Court — apply by 30 November 2018.

The Supreme Court is offering students the opportunity to have a live question and answer session with a Justice from their own classroom. These sessions will run between the months of January to May 2019 and offer students with a keen interest in law a unique chance to meet and speak with a Justice.

In order to apply, please complete the application form on the UK Supreme Court website, and send toenquiries@supremecourt.uk quoting ‘Ask a Justice’. The deadline for submission is 30 November 2018.

Sexual Harassment at the Bar

Gresham College — 7 pm, 29 November 2018

Professor Jo Delahunty QC continues her series on the Family Justice System at Gresham College in Holborn with a talk on the recent

“seismic change in the willingness of women to speak out about sexual abuse they had suffered at work and the willingness of others to hear and act on it. This year (2018) saw the creation of a #metoo movement called ‘Behind the Gown’ created by a group of barristers committed to tackling sexual harassment at the Bar.”

This lecture frankly confronts the anecdotal evidence and suggests ways in which we can learn from it. Click here for further details.

That’s it for this week. Thanks for reading. Watch this space for updates.

This post was written by Paul Magrath, Head of Product Development and Online Content. It does not necessarily represent the opinions of ICLR as an organisation.

Images: selection of proper cheese from Shutterstock; image of Lord Chief Justice is taken from his Annual Report 2018; images of live streamed Court of Appeal sittings copied or screenshot from Judiciary website.